When it was (Frank) Miller Time

So, a few things up front:

Frank Miller Time ended with the start of Desert Storm.

This is not an arbitrary stopping point for one of comics’ greatest creators and voices, but a meaningful turning point in the American zeitgeist, one that pivots ever so slightly away from the America that made Frank Miller “Frank Miller”.

If you know MIller’s work, and in turn know his presence and personality etc., you also probably know that he went bonkers after 9/11. Bonkers in a very reactionary and hateful way.

He has stated “I’m not a conservative, I’m a libertarian”, which is to say he’s a kook, and he is also an old man, one who thrived in a certain moment, and who, as stated, went off the rails.

I’ll explain a little bit more about the why of his totally losing it and pivoting to a truly dark and regrettable place… one that he has seemingly pivoted back from to some degree at least… and how it fits into the pattern of his work and psyche he’s shared publicly, but know that I’ve had little to no interaction or engagement with his later work, anything post Miller Time.

So, with that out of the way, just who is Frank Miller, and why was the post Vietnam, pre Desert Storm Reagan America “Miller Time”?

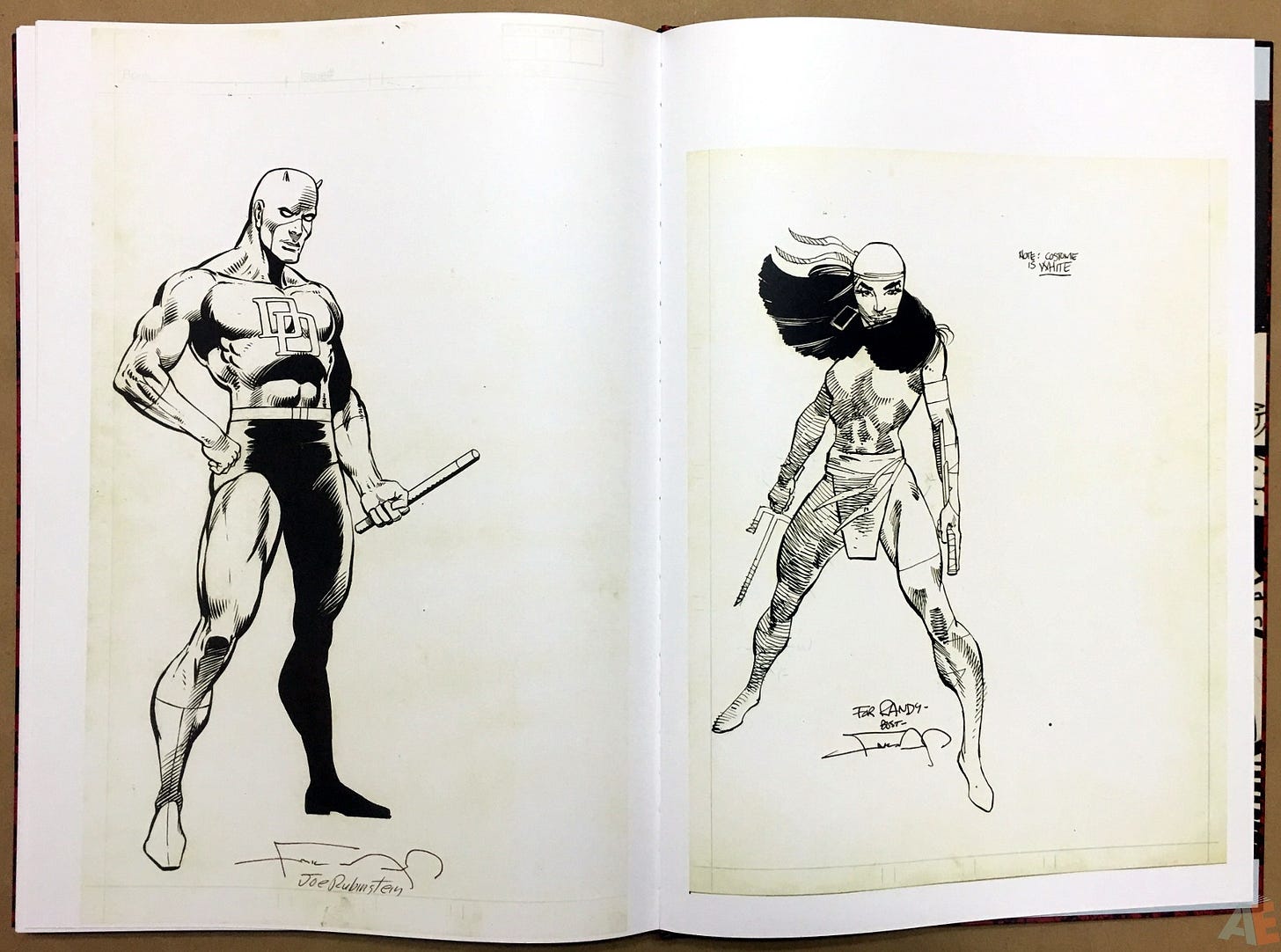

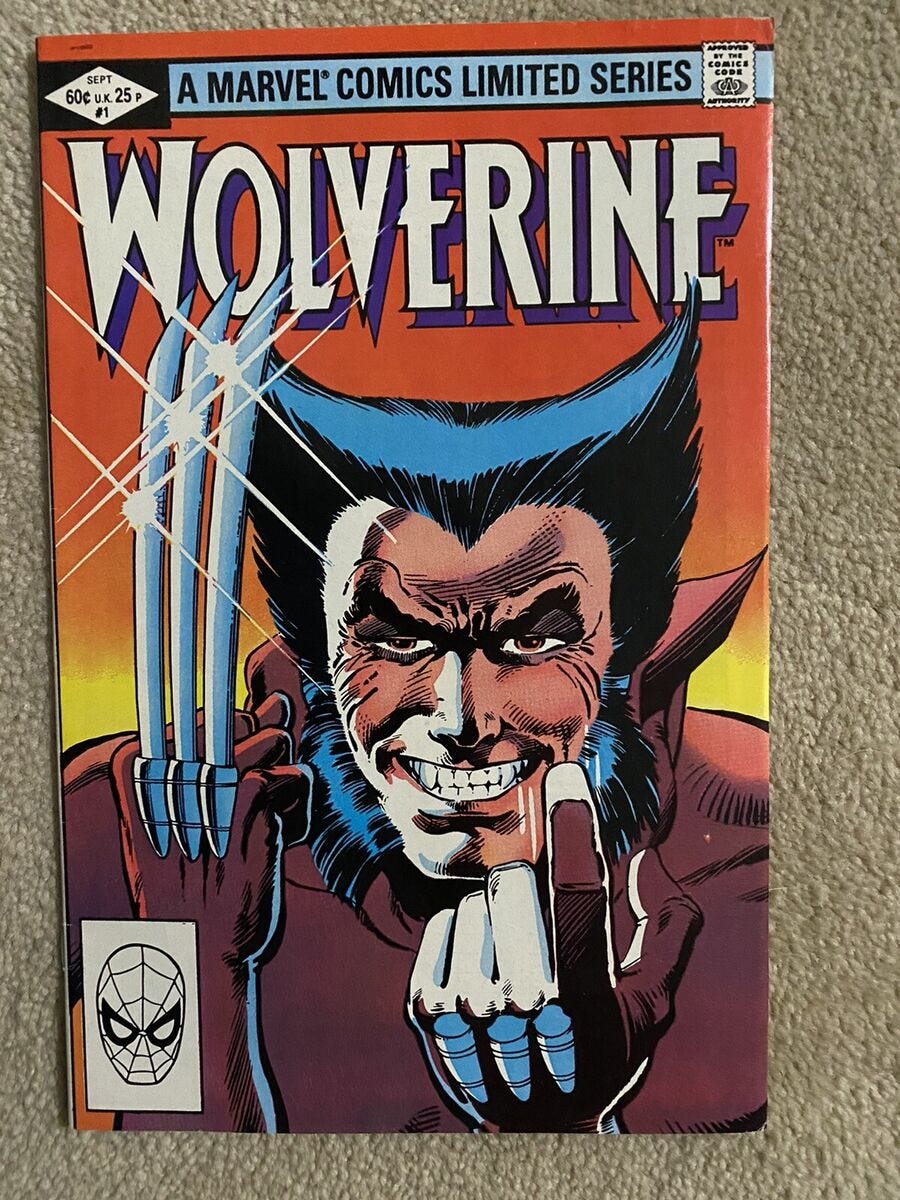

Frank Miller is a writer and artist best known for his work on Batman, Daredevil and Wolverine, mainly his work on making them cool and human.

While X-Men writer Chris Claremont made the X-Men into comics best soap opera, making them cool, horny, and compelling, Miller made comics gritty.

Gritty is, for some people, a loaded term.

They think gritty means pointlessly or self-indulgently edgy, an excuse for gratuitous cruelty in the quest for realism, and yes, sometimes it does work out that way, but that’s not the point.

No, grittiness has one point, and one consequence.

The point of grit is visceral satisfaction, both in mood and action.

The consequence is believability.

When grit is done right, it places the story in a more visceral and grounded style of storytelling. Even when grit is hyper-stylized, like say for example the Sin City movie, which is based on Miller’s comic of the same name, it is gritty not just because of a grimy aesthetic, but because the action of the story is immediate, and consequential.

This is what makes both creators and the audiences, lazily, confuse gritty with realistic. For something to be gritty, truly gritty, it needs to be believable, consequential. and visceral, and those three things add up to actions and characters that are grounded in cause and effect.

But none of that makes a character like Batman actually more realistic, it just makes the character more believable, but realistic and believable ate not the same thing.

The thought experiment of “What would Batman be like in real life?” starts with the wholly unrealistic premise of Batman, and works outward from that into “how can the fictional be realistic within the premise of its fictional existence”.

The result of that line of thinking ends in grit, pure, gravel in your teeth grit.

Parts of “gritty” reflect the emotional hyper-realism that exists in a heightened reality that is identifiable and relatable, and in turn become realistic, because they match the space they exist in, and because they are relatable. When done well, the way Miller does it, the grounded nature of this style of storytelling creates believable emotional responses in unbelievable situations.

The entire genre of Film Noir is grit.

Robocop is grit. Every character in that movie has utterly human and knowable motivations, and the violence is consequential and reflective of the stakes of the story, but no one says it is a realistic movie.

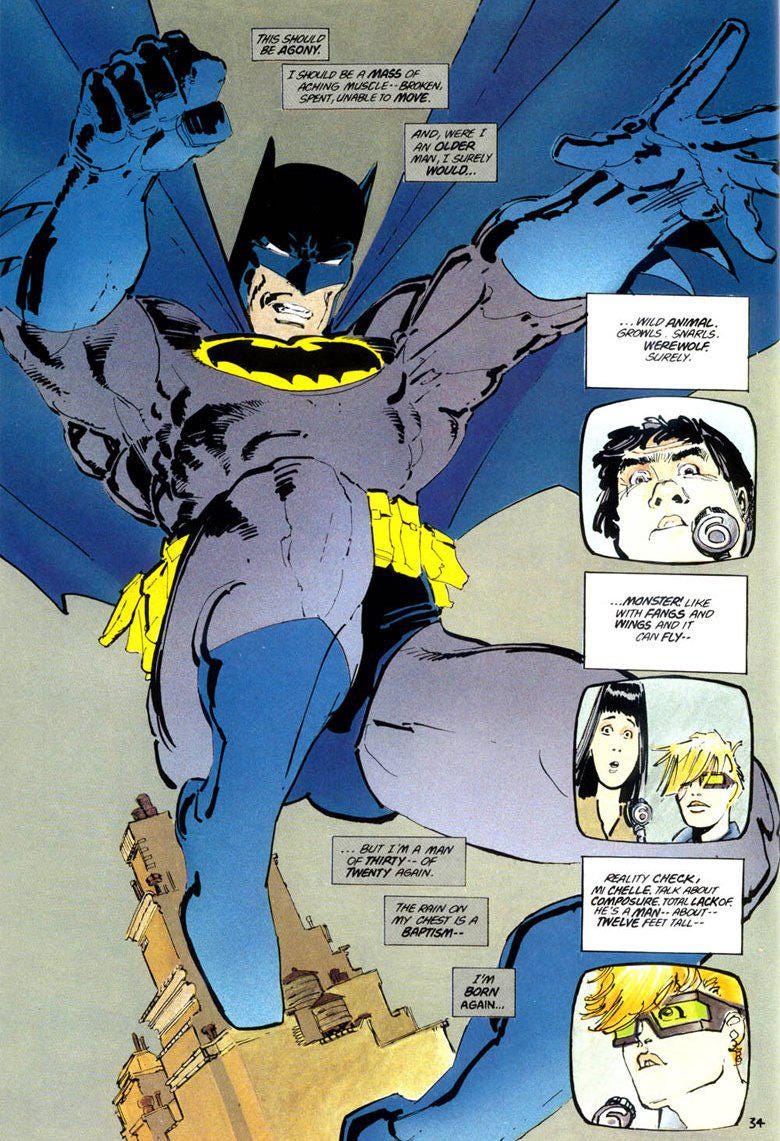

An aging Bruce Wayne putting the cape an cowl back on because, internally, he can’t turn his back on the city that needs him, is as gritty as it comes, and it is the premise of Miller’s magnum opus The Dark Knight Returns.

While Frank Miller made Daredevil cool, whereas before Miller Matt Murdock the blind lawyer/vigilante was just a b-list Spider-Man, and he drew the four issue Wolverine mini-series, written by the aforementioned Chris Claremont, and helped make Wolverine as culturally ubiquitous as he has become, The Dark Knight Returns is, and always will be his greatest work.

This is in no small part because he wrote and drew it, with inks by Klaus Janson, Colors by Lynn Varely, and letters by John Costanza, giving the book a singular direction that makes it more than the sum of its individual artistic components, and because the books exists in a space where the characters can exist in a world of consequence.

Monthly superhero comics are cyclical storytelling. Characters die, and come back, plots are recycled, and characters can learn and change, until the cycle starts over, and they are re-launched, retconned, or factory reset in any number of other ways, because the cycle must begin again, new readers must be given a chance to hop on, time must stagnate, and the machine of IP management must chug ever onward.

And this is why, in the loose quote of Frank Miller, “Comics are the bastard red headed step-child of literature”.

He said that in the single best thing that the Ben Affleck Daredevil movie gave us, the hour long special feature documentary…

Wherein he talks about not just the how and why of making Daredevil cool, but of the possibilities in comics, the meat of human experience that informs these characters att heir core when their stories are told well, and how they are made of the same stuff of any story.

All of this is most clearly on display in his aging Bruce Wayne, which is in itself a novelty as these characters are not allowed to age, and if they do age, then not too much or for too long.

But art always exists in conflict with itself, and loving these characters means you always wonder what if (hence Marvel’s What If… series, where premises are changed, characters are different, and where usually everyone dies at the end), and that wondering and pushing back gave rise to what DC Comics calls “Elseworld”, or better still “Imaginary Stories”, which yes, ever fan and creator ever has said, “but they’re all imaginary”, stories that are non-canonical asides.

Anyhow, all of this is to say that Dark Knight Returns is not an official part of the Batman timeline/continuity, the endless cycle of stories that make up the character’s reality… though Dark Knight Returns is so beloved that it exists as a kind of Ragnarok, that even though its time has passed (more on that shortly), it exists as a kind of emotional truth that “this is how Batman ends”.

You see, in the mid 80s, before the 1989 Batman movie redefined what the public knew about Batman from the 1966 TV show, Frank Miller told the story of an aging Bruce Wayne who had retired from being Batman.

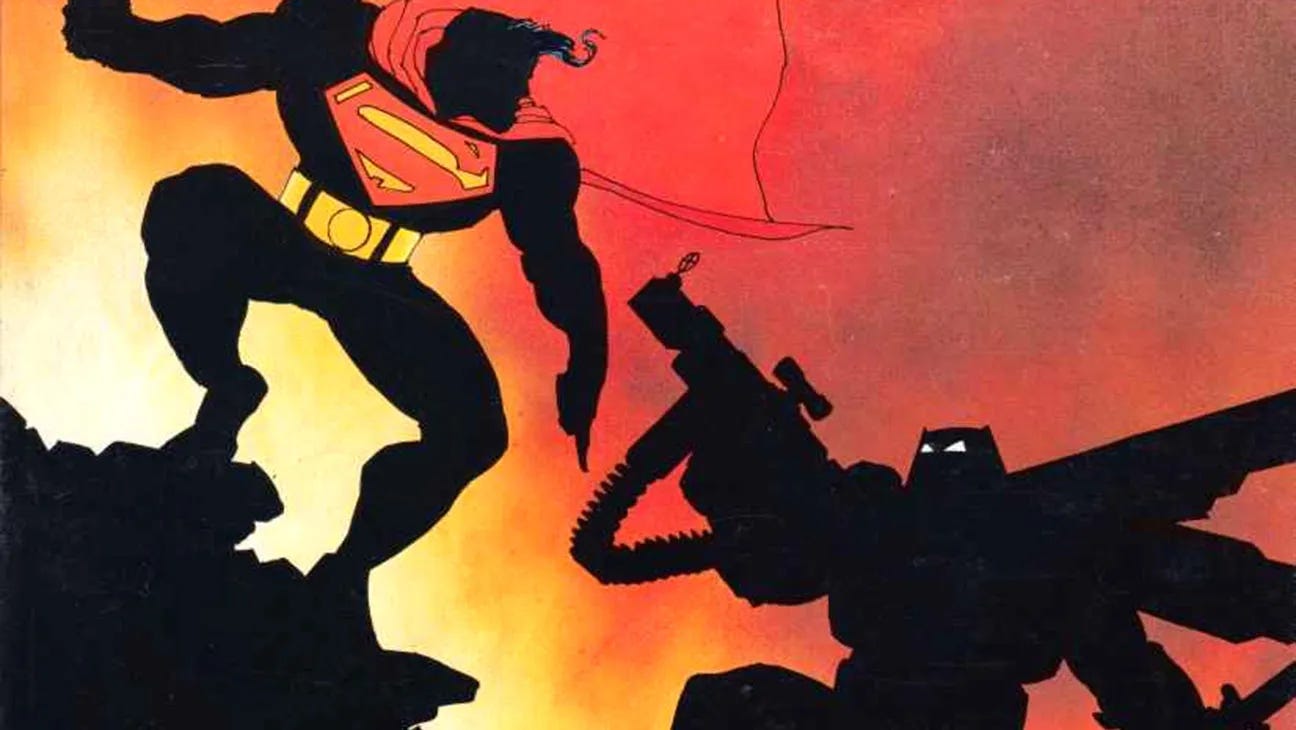

He did this due to a government crackdown on masked vigilantes, brought on by the Reagan administration during the Cold War, and enforced by Superman. Yes, in this story that is firmly set in a 1980s Gotham that is a pre-Giuliani New York, we are in the same Reagan’s America that America was in.

This is MIller’s Time (and place), the America that is still processing the psychic wounds of Vietnam, before the ghosts of interventionist failure were exorcised by Desert Storm, the America of poverty, drugs, and anger at a system that seemed hell bent only on failing the masses, one that seemed to encourage real life vigilantism like the December 22nd 1984… hey, my third birthday… NY Subway Vigilante Bernie Goetz, who just shot at some black kids because he was a fearful bigot, a time where union busting, deregulation, and automation were destroying teh working class, whiel the upper class played reckless games of chance with stocks and massive consumer debt.

This was Miller Time, this was the America of the reader, and the America of Gotham City.

It wasn’t, “what if Gotham city existed in our world” it was, “what if our world existed in Gotham city?”

And in that city, in Reagan’s Gotham, while Bruce Wayne was old, and broken down, and while it was even more against the law than it always had been, this Bruce Wayne saw that his city needed him, and that he still needed to keep his promise to his dead parents, and did the only thing he could do in the face of what he saw before him.

He put the cape back on and got back in the fight.

Frank Miller is a New Yorker. More than a libertarian kook and a cranky, successful old white man, he’s a New Yorker… who got mugged a lot in the 70s and 80s.

If you want to understand Miller the artist, you have to understand those things first, and that he’s also a nerd like everyone that loves comics is.

He’s a nerdy New Yorker who got mugged a lot while living in and around the city in the 70s and 80s, and he’s someone that believes in the idea of justice.

He made Daredevil a ninja, and Wolverine a samurai because ninjas and samurai and martial arts are cool nerd shit, especially in the early 80s, and he made Batman a grizzled old Eastwood-esq figure, because fuck Ronald Reagan, fuck the yuppies, and fuck these fuckers that keep mugging me.

(My words, not his, but it’s in the text.)

(As a quick aside, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles are a kind of parody of Miller’s Daredevil. The radiative material that blinded Mat Murdock fell in a sewer and mutated the turtles. Daredevil fights the ninja clan The Hand, the Turtles fight The Foot. Matt’s teacher is Stick, the Turtles teacher is Splinter.)

With all of that anger and pathos, and backdrop, with space to tell a story not bound by continuity, Miller was able to game out and play out what the believable and ground progression of Batman and his villains would be. What would realistically, in the the heightened reality of Gotham City, happen with Two-Face, The Joker, and Bruce himself.

What serious, honest, and grounded stories could you tell when the characters were let off the leash of continuity, not for pure sensationalism, but for the sake of finding something human and consequential.

You see, on top of everything else, Miller, like everyone that truly loves these characters, is a bit of a romantic. This pairs with his libertarianism, of course, but he believes in the idea of the beauty, and power, and goodness that people are capable of. He says as much and shows as much in his work…

And yes, him being a New Yorker who got mugged a lot does in fact explain why he went cold ass bonkers after 9/11, and we’re all faced with the disappointing juxtaposition of someone who believes in the best of people while also going full tilt reactionary.

(We see it all the time, because you can see the best is ‘some’ people, and hate all sorts of other people.)

The Dark Knight Returns is a story of hope.

Yes it is the truly American “one man can make a difference” version of hope, but it’s a story of hope none the less. It’s also the story that gave us Batman fighting Superman.

Not winning, not beating him, but standing up to him and making him fight for every inch.

It’s not Rocky, Batman doesn’t go the distance.

But it’s not about that. It’s about a man fighting a god, and in the end, in that story, it matters.

And almost 30 years later we’re still talking about that story, so clearly…

It matters.