Die Hard is a Christmas movie.

There is a lot, and I do mean A LOT around this debate, because people have very strong feelings about Christmas.

For example, I don’t particularly like Christmas, and haven’t since my mid-20s.

You might even say I hate Christmas, because I have in point of fact said many time that I hate Christmas.

I’m an atheist (almost one of those militant asshole ones) with a birthday 3 days before the holiday, who worked a retail job for 7 years that was open 365 days a year, and celebrating the day has usually made me feel profoundly lonely for reasons that I am opting not to share here but are personal and valid.

And while we’re talking about feelings, likes, and dislikes, etc. while I enjoy Die Hard quite a bit, it’s not one of my top ten favorite movies, it’s not even my favorite John McTiernan movie (that would be his legendary flop The 13th Warrior, a dumb sword fighting movie that I love, followed by Predator because yes, the same guy directed Die Hard and Predator… and Last Action Hero, which I hate more than Christmas).

I have much more skin in the “Christmas is terrible” game than the “Die Hard is the best action movie of all time” game, so this piece is not about celebrating a seminal and genre defining movie that is essentially perfect.

No, this is about what it means to be a Christmas Movie, and why it matters that Die Hard is one.

Now this is going to sound obnoxiously self-important, and utterly inane, but I am one of the people responsible for “Is Die Hard a Christmas movie?”

You see, that 7 year job I mentioned earlier, if you know me, you know it was Blockbuster Video, a place where, every holiday season we would have to make space on and populate a section of the new release wall with holiday/Christmas movies. Now, we had a list, but we also had the freedom to put what we wanted up there, and every year that I was there we would put up Die Hard.

It wasn’t just my store,. this was something extremely common, and combined with TV programming coming up with showing Die Hard around the holidays (I’m sure that happened), the era of the video store was the beginning of this conversation.

Now, yes it did start with a little bit of tongue in cheek irony, and a lot of clever awareness like, “You’d never think of THIS MOVIE as a Christmas movie, because it’s an action movie, and not It’s a Wonderful Life or Christmas Story” but there was also an understanding that while we were putting up movies that took place during Christmas (Shane Black’s writing and directorial offerings like Lethal Weapon and Kiss Kiss Bang Bang etc.) because we needed to fill the space, there was always a difference between those movies and Die Hard.

(And also Gremlins… that’s the real debate, is Gremlins a Christmas movie? There’s still meat on those bones).

And if you doubt that, we had actual conversations about it at the time, yes we discussed “Takes place during vs. is a” while determining said space filling.

None of this is new.

But everything old is new again, and with different intensities and focal points.

One way of seeing Die Hard as a Christmas movie is as aggressive irony and infusing a time of peace and love and togetherness with edge macho action bullshit edginess; the denial of the wholesome, the compassionate, and the soft.

It’s the question of, “Why can’t we have this one thing? Why can’t Christmas simply be CHRISTMAS?”

And it’s a fair question, but like any question of purity, your celebration and your cinematic holiday canon can exist without including it, while also not denying it to those who like it, want it, or need it.

Christmas movies, and Christmas itself, often times exists in a bittersweet space. Christmas Story, Home Alone, It’s a Wonderful Life, Miracle on 34th Street, all of these movies have some darkness to them, and they either lead with, or ultimately find joy, and/or an embrace of the sacred.

There is joy and compassion at their heart, and the miraculous.

They feature Santa, miracles, and family coming together, and they all exist and occur because of the holiday.

And you know what?

That sums up Die Hard.

It is, at it’s heart, the story of a man traveling across the country to reconnect with his estranged wife and children over the holidays. That’s it, that’s the emotional core of the movie.

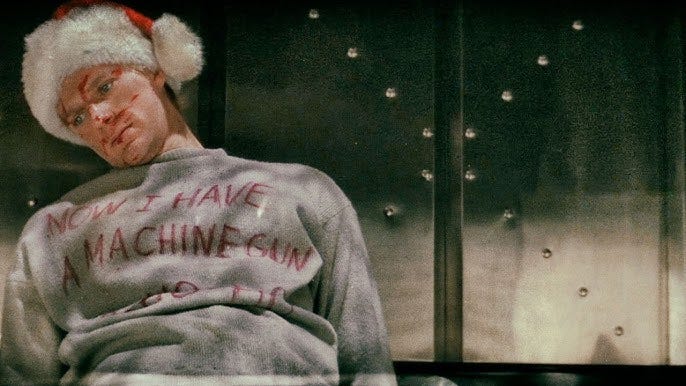

If he didn’t kill a gaggle of Eurotrash thieves pretending to be terrorists ( which included making a list and checking it twice), no one would doubt its Christmas bonafides.

But since it’s an action movie, the fact one man does all that killing and saves the day isn’t seen as a Christmas miracle (well, Sgt. Al Powell overcomes his own trauma to be able to shoot people again and gets the final save the day kill, and Argyle also runs a dude over), which it is because of the scope of the movie and the fact he’s a pretty normal dude, and the fact he reunites with his wife at the end of it, those are seen only as the action genre tropes and not the Christmas genre tropes.

As such, people ignore the text of the movie, its symbols, and its active symbolism in favor of its spectacle, which in turn serves as a kind intellectual and emotional classism, not quite a high art/low art manufactured divide, but an assumption that an action movie cannot be emotionally resonant due to its focus on, well… action.

And again, it is a fair question to ask why Christmas can’t be spared from the violent, from the vulgar, and from the vicious, all things that Christmas is supposed to provie succor from.

But for some people, Christmas is a time of loneliness, of isolation, and of heartbreak. It’s a time of year where you are told to be with the ones you love, but if they can’t be with you, or you can’t be with them, or if they’re gone, or if you are not close with your family for any reason, then, all that’s left is commercialism, a spotlight on what’s missing, and religion… and if you don’t have religion, then it’s a day where you are forced to see the absences in your life and your heart all because of a make believe wizard baby’s birthday.

That is, of course, a pretty grim reading of what’s supposed to be a wonderful time of year, and of togetherness, but if you can’t share in it, it’s only exclusionary.

And the thing is, you can’t escape Christmas, but you can carve a piece of it out for yourself. You can find parts of it that you can call your own, and traditions you can make.

You can celebrate hope and coming together in the darkest time of year in the ways that sustain you and give you joy.

Christmas, the American cultural idea of it, the faith around it, and the culture of it, is one that is prescriptive and demands conformity. It is the group think of faith, commercialism, and the nuclear family rolled together into a monolith of performative joy, and if you think it’s not, ask yourself why people are just as vehemently against Die Hard being a part of Christmas as the most annoying film bro you know is for it.