David Lynch died from doing what he loved, smoking.

It’s a rough way to go, but he willingly paid the price for indulging in his love and passion, and really, what can any of us say to that?

I’ve only seen Mulholland Drive (not to be confused with Mulholland Falls) once, and if you asked me to tell you what happened in it, I wouldn’t be able to say much more than something about a little person, Naomi Watts. and a guy in a cowboy hat. I used this experience, more on what that experience was later, as a jumping off point for my assessment of Lynch when I was in my 20s working at a video store:

“All of his stuff is basically just a midget in a cowboy hat.”

The thing was, even Lynch fans thought it was funny.

Also, I’ve only seen a scant few of his movies, I’m not a Lynch expert by any stretch.

It’s easy not to know what happened in a David Lynch movie, and there isn’t a profound validation of his art coming as a followup or rejoinder like, “because life doesn’t make sense.”

No, it’s easy to not understand or track what’s happening in a David Lynch movie because…

The first time I touched a boob I was “watching” Dazed and Confused at a cast party, making out with my high school girlfriend. That movie, Dazed and Confused, is about teenagers in the 70s on the last day of school.

Directed by Richard Linklater, it’s a slice of life comedy (loose dramedy) that is mostly to blame for the TV series That 70s Show, and has a really good soundtrack, even though it includes Ted Nungent.

It’s a movie filled with young, attractive people playing in or around(ish) their own age, depicting the various surface layers of adolescence in transition. It is, or was for a while at least, the kind of thing you would think of when you think of a teenager.

Dazed and Confused came out a few years after the season 2 and in turn (for 25 years at least) series finale of David Lynch and Mark Front’s seminal TV show Twin Peaks. Set in the fictional western Washington town of Twin Peaks, and me, having younger parents and it being a cultural juggernaut, as a child I knew about Twin Peaks, or at least I knew it as a force of cultural nature, especially since it was basically just a few miles away from home.

My childhood experience seeing bits and pieces of it, and wanting my parents to explain it to me, which they did to the best of their ability, was as follows:

“I have no idea what’s going on.” -Homer Simpson

As baffling and incomprehensible as it was to young me, I don’t think I’ve ever had any questions for David Lynch, save for the question we all had in the 90s, “what was going to happen?”

My personal variation of that question was, ‘How’s Annie,” but only because I did watch the entirety of the last episode (my parents taped it) and I was, as was everyone who watched it, left with square jawed, handsome Hero FBI agent Dale Cooper possessed by an evil spirit, staring into a mirror, using too much toothpaste to assmuedly brush his teeth, then smashing his forehead into a mirror, and asking that same question over and over again.

“How’s Annie? How’s Annie? How’s Annie?”

That, and the opening credits theme song will always be my most indelible Twin Peaks memories.

Annie was played by Heather Graham, who I would mainly know from the second Austin Powers movie and from her role as Roller Girl in Boogie Nights, a movie about porn in 70s, directed by Paul Thomas Anderson.

There is nothing particularly Lynchian about the way I’m writing this article, this kind of free association and topic jumping is far too literal, and while it might seem weird for weirdness sake to mention touching a boob, nothing about Lynch’s work was weird for the sake of weird.

David Lynch was American.

He was truly and distinctly American, and he was interested in square jawed and handsome leading men, gorgeous movie starlets, and he was interested in American places, and Americana, not out of irony, but out of connection.

He was, as his work shows, also famously interested in the underbelly of America, and the whole of the American identity. Shame, perversion, vulgarity, the violence of desire, and the burdens of both repression and excess run through many of his movies, as do colorful faces and colorful weirdos.

The visceral and the ugly was ever present, as was the idea of the movie, and the TV show. These more of communication are artifacts and forms, their existence is defined in shapes and boxes, but their contents can be anything. It’s nothing new to say/point out/remember that the movie screen is a canvas.

Lynch loved movies, and he didn’t seem to hate conventional storytelling, but the latter didn’t meet his artistic needs. I haven’t seen all his movies, but he tried his hand at things that were not nearly as Lynchian as… well… what we think of when we think of a David Lynch movie.

Dune was supposed to be the next Star Wars (Lynch was also up for directing Return of the Jedi), and while it wasn’t that, it did manage to be very him, in that it was interested in the ugly and violent truth under the facade of beauty, normalcy, and convention. It wasn’t Lynchian, but it was Lynch.

Mulholland Drive is a Lynchian fucking movie… I think.

That’s an exaggeration, I saw most of it, we saw most of it.

Or at least just enough for me to confabulate the little person and the cowboy into one character.

I had this downstairs neighbor in the spring of 2002, and she was great, I was super into her.

She was attractive, a few years older than me, had great movie and TV taste, and was an absolute disaster of a person (so just my type), but she was also 22-23, so in so many ways she was really just the kind of person I tended to know who was in their early 20s.

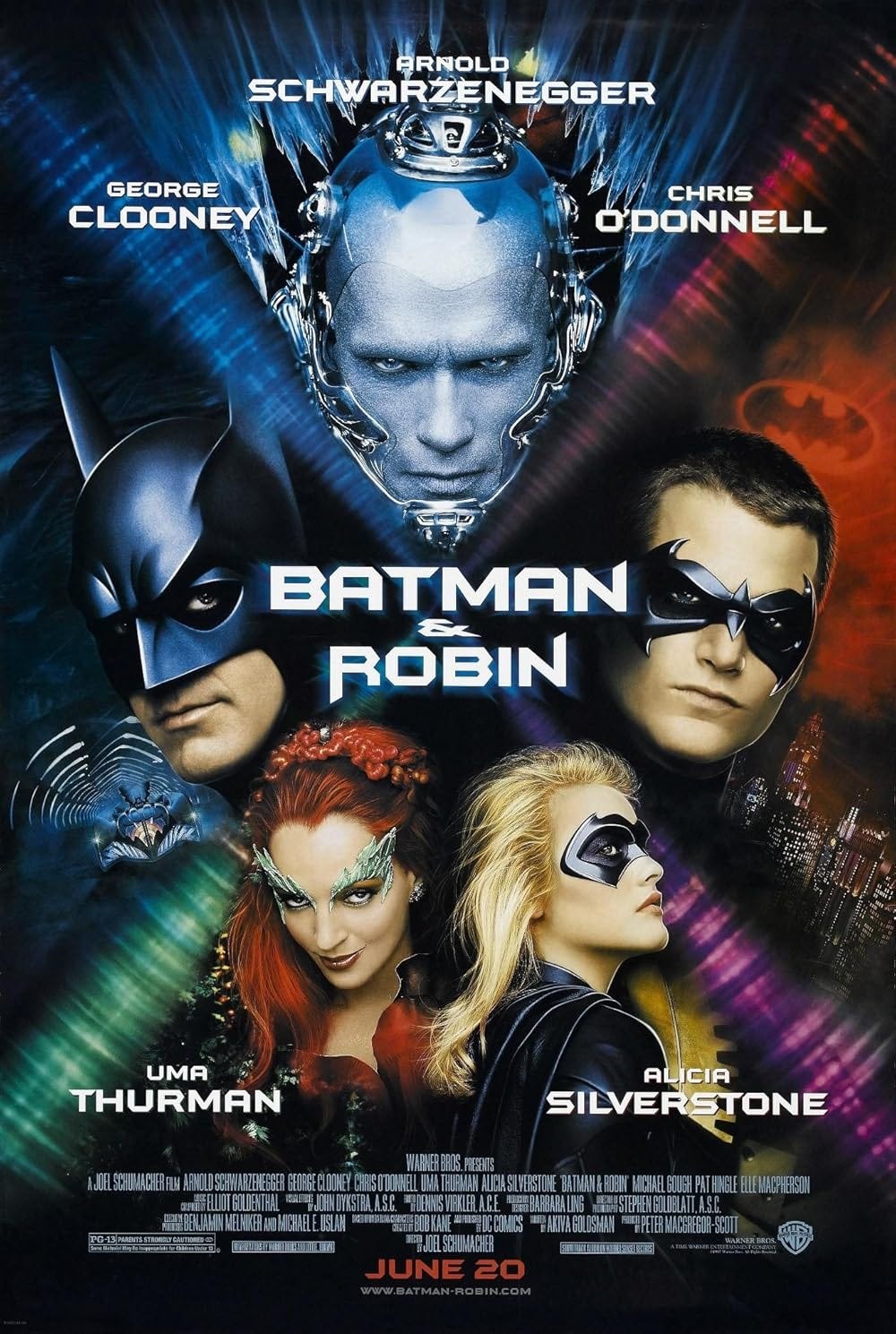

One of the last times I talked to her, she was coked up (“Max he said he never tried coke before, so we did a bunch of coke”) and telling me about how she and this guy she was seeing (she and I had our moments, but she didn’t want what I wanted, which was a relationship… also, she was a mom, so god damn could my life have gone differently) were ‘planning’ a Batman themed wedding. And let me be clear, it was a Joel Schumaker style Batman wedding.

Because really, what other Batman wedding would you come up with in that situation?

I’ve known a lot of David Lynch fans and of all of them, she’s the one that was the most like a David Lynch character, in that a part of her was always spiraling into the underbelly of the American experience.

Or I see her that way because that few months of knowing her was a truly surreal stretch of time for me. It was probably more Coen brothers than Lynch, but it was a crazy stretch.

Anyhow, there’s making out while watching Dazed and Confused and then there’s “other things” while watching Mulholland Drive, and no, they are not the same. But given Lynch’s interest in the carnal, and the idea that you are ostensibly doing one thing, but really, something else entirely is unfolding internally and externally, they’re more connected than their superficial components.

To Lynch in both instances, the movie would be the framing device for the story of our actions, but the movie would also matters just as much. And while I’ve leaned into the surreal and nebulous experience of Mulholland Drive being on in the foreground, then eventually the background, my experience with Dazed and Confused was the far more surreal of the two experiences, drunk with unfettered and untested hormones, heat, and darkness, Dazed and Confused far more Lynchian than being drunk on Absolute Vodka… that she had to buy because I wasn’t quite 21 yet.

I don’t remember which podcaster said it, I think it was probably Andy Greenwald from The Watch, but it might of been his co-host Chris Ryan, but they pointed out that a David Lynch movie would have things you’d see in other movies, but that it would also include dreams and asides because he thought they were not just worth screen time, but necessary for his art and likely the priupose for it, and that got me thinking.

This isn’t a particularly smart thing to say, and I said it in a way up above, but more than surreal weirdness, maybe the Rosetta Stone for Lynch is that the ephemeral and metaphysical, as well as the tangible are both equally real in a Lynch movie.

David Lynch, the American, could have died in Vietnam, and that would have been a more natural conclusion to his story than what ended up becoming his life.

America is a weird place full of weirdos and kooks, and it always has been. American spiritualism, occultism, and mysticism have always been tied to expansionism, war, and a rejection of the superficial, or at least exploration of what’s under the surface of America.

These things may not seem connected, but there’s a reason Scientology and biker gangs started out here, why the inventor of solid state rocket fuel was into sex magic (okay, fine, yes, it this case it’s spelled sex magik), and why we’re dealing with a rehash of the Satanic Panic, and why this burger loving, chain smoking, director found his way to transcendental meditation… which is one of America’s many, many, oh so many cults.

The spiritual, the metaphysical, the unknown and unknowable are all just as real in America as any other element of our cultural history, including rebellion and independence. He’s part of that tradition, especially because he grew up in the post Word War 2 America that gave rise to what I listed above, in no small part because of a uniform focus on getting Americans to be happier by conforming.

And without being too trite, while no one wants to hear us describe our dreams, our dreams and our dream logic are a real part of ourselves.

Telling a story with dream logic, or more so, using the tools of storytelling to create and present dream logic means that all the parts of the dream matter just as much as what we, in the telling of our dreams, deem to be the important part. If anything, what we try and minimize in trying to hold on to the idea of the dream, reveals something powerful about ourselves.

The act of saying “it was just a dream” becomes an act of self-definition, just as surely as putting too much emphasis on the dream

It’s just like how Lynch never wanted to reveal who Laura Palmer’s killer was in Twin Peaks because to him the “who done it” wasn’t important, it was just the shape and not the contents, also because it was everyone’s fault. So no, it wasn’t important, not compared to the what and the why; not the why of the murderer but the why of murder in general.

I’ve watched the first two seasons of Twin Peaks as an adult a couple times, and I watched The Return with the slightly disappointed, but not at all surprised curiosity of someone hoping for more Twin Peaks and less DAVID LYNCH, and I appreciated it and accepted it for what it was.

I think it might have been the best thing he did, but when you let someone make an 18 hour art house movie where you get to hold the audience hostage with their expectations and dedication to a story they’ve waited 25 years for, and you have an audience that has grown with your style and sensibilities, in some ways you’re playing with house money.

Anyhow, it’s not that I like David Lynch… I mean, I bet I would have liked him, he seemed like a cool dude… it’s not that I like the Lynchian Lynch, it’s that I respected him and was interested in him, but he wasn’t my favorite.

He was a weird dude that made weird movies that were normal enough to be accessible to the average person, especially the average American if they took a chance, especially because they, like he, were often horny as hell, which is why I talked about touching boobs and hooking up with my neighbor.

I’m better for being challenged by his work.

So let’s all have another cup of coffee, and let’s have another piece of pie, because the monster’s been us all along, and it always will be.